How ARC CBBC brings together materials science and chemistry to improve sustainable coating removal

‘There's a great synergy between us. When I look at a specific material, I always ask myself: how can I break it down? And Michael can actually design functionalities that make it easier to do just that.’

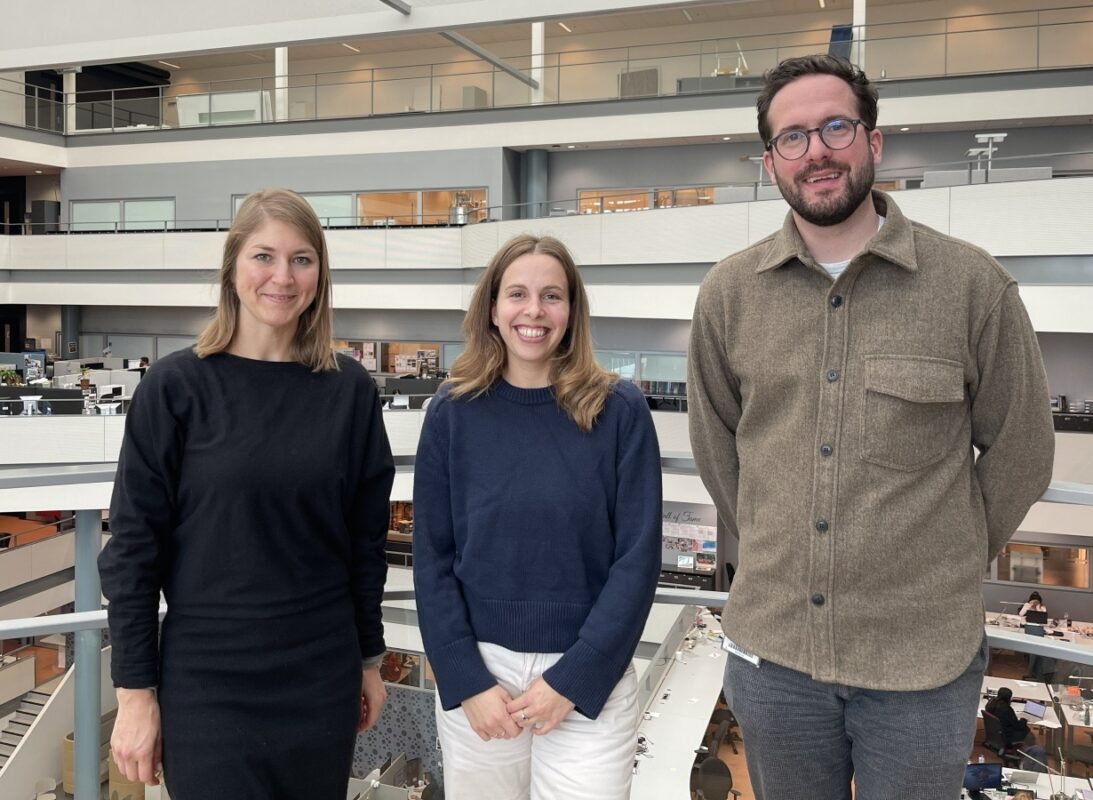

When chemists Ina Vollmer and Michael Lerch began collaborating on a project to develop more sustainable methods for removing coatings, they were addressing a problem that affects everyday objects – from furniture to aeroplanes. Their complementary expertise – Ina's focus on sustainable chemical recycling and Michael's background in synthetic chemistry and materials science – proved an ideal combination for addressing the challenge of making coatings removable at their end of life in a sustainable way.

Their ARC CBBC project, in partnership with AkzoNobel and BASF, aims to develop novel methods for the selective removal of coatings: a seemingly small but surprisingly significant challenge in the creation of more circular material cycles.

The researchers

Ina Vollmer's path to sustainable chemistry began as early as secondary school. Initially, she studied process engineering, with the idea of explaining climate-related issues in the chemical industry to a broader audience. She soon realized, however, that her talents lay more in science than in journalism. After completing a PhD on heterogeneous catalysis and spectroscopy to study methane valorization, she shifted her focus to plastic recycling during her postdoctoral research. Six years later, she continues to work on chemical recycling, with a particular emphasis on using mechanical force in a ball mill, where the grinding spheres themselves activated, rather than relying on heat to drive chemical reactions.

Michael Lerch's journey began as a synthetic organic chemist, working on molecular machines and photo switches: molecules that can move and respond to light and other stimuli. However, he was dissatisfied that his research rarely extended into materials such as plastics and coatings. He therefore enrolled in a postdoctoral programme in the US focused on bioinspired materials. There, he developed new types of coatings featuring carpets of tiny hairs, similar to the cilia in our lungs that keep our airways clear, which he could set in motion in programmed ways. ‘I quickly realized that, as chemists, we create new molecules, and that is extremely powerful in materials science,’ he says. ‘It allows us to design materials, such as coatings, with completely new properties.’

Today, his work focuses on implementing responsive chemistry in coatings for applications in robotics and medicine.

Completing the team is postdoctoral researcher Phoebe Lowy, who brings expertise in soft matter science and a focus on sustainable chemistry. She completed her first postdoc investigating the thermal and mechanical properties of novel biodegradable plastics.

The challenge

The scale of the problem Ina and Michael face is immense. Coatings are everywhere – from paint on walls to high-performance finishes on trains or cars – and they are designed to be extremely durable and resistant to removal. While this durability is beneficial during use, it becomes problematic at the end of a product's life. Furniture, for example, is often discarded rather than recycled, because sanding off coatings is really cumbersome, as Michael explains. ‘We need new solutions that allow coatings to be removed and replaced more easily.’

For high-value applications like those in aircraft, the current solution is far from ideal. ‘The exterior coatings of aeroplanes need to be reapplied every seven years or so’, Michael points out. ‘In order to do so, however, you need to soak the entire aeroplane in DMSO [a chemical solvent, ed.]. It works, but it is far from ideal.’ Another advantage is that this process is not only environmentally problematic but also costly.

The research

Ina and Michael’s project introduces a novel approach to this challenge by developing coatings that can be removed through a combination of mechanical force and chemical triggers – what they call a ‘mechano-chemical de-coating strategy’.

‘Through the mechanical force, some moieties within the polymer – the polymer that makes up the coating – open up,’ Ina explains. ‘This induces a chemical change in the material, releasing smaller molecules that promote the breakdown of the coating.’

The second approach involves creating ‘links that preferentially break’ when force is applied, causing the polymer chains to shorten, thus making the coating easier to remove.

For large objects such as aeroplanes, the researchers envision practical application methods such as ultrasonic probes that can be moved across the surface (similar to painting but for removal) or rollers that apply force to activate the delamination process.

Complementary expertise

The collaboration between Ina and Michael exemplifies ARC CBBC’s strength in bringing together researchers with complementary expertise. Michael's group has recently ventured into mechanophores – molecules that respond to mechanical forces – while Ina specializes in polymer degradation through mechanical means such as ball milling. ‘That's a perfect combination,’ Michael says, ‘where basically the synthetic expertise from my side and Ina’s ball milling and polymer recycling experience converge seamlessly.’

This complementary approach allows them to tackle the problem from multiple angles. Michael designs and synthesizes materials with specific responsive properties, while Ina tests and optimizes methods for their efficient breakdown. ‘Michael is more focused on chemistry, and I’m more focused on application and recycling potential,’ Ina explains.

Industrial relevance

The involvement of industrial partners AkzoNobel and BASF brings essential practical perspectives to the research. AkzoNobel, a major player in the coatings industry, lends its expertise in high-performance coatings, while BASF contributes its knowledge of coatings used in applications such as paper cups, where recycling is particularly challenging due to the difficulty of separating plastic linings from paper. The industrial partners help ensure the research addresses real-world needs and constraints.

Environmental impact

The project contributes to sustainable chemistry in multiple ways. Its primary aim is to reduce the use of toxic solvents and minimize waste from coating removal processes.

‘Removing coatings often requires large amounts of solvents, many of which are toxic and wasteful,’ Ina explains. ‘Sanding coatings produces micro- and nanoplastics that are harmful to factory workers and generate significant waste. Avoiding these processes offers a clearly greener solution.’ Additionally, the research could improve recycling rates for valuable materials such as metals.

The role of ARC CBBC

For Ina and Michael, ARC CBBC provided the framework that made their collaboration possible. While they might not have sought each other out independently, the consortium brought them together and facilitated their partnership. Beyond matchmaking, ARC CBBC offers the structure needed to manage complex collaborations between academia and industry.

The project includes quarterly meetings with industrial partners, where researchers and companies exchange ideas and feedback. The scientists value the opportunity to test their work against practical constraints, while companies gain early insight into research that may inform future product development. ‘It's a valuable addition for the people working on the project,’ Ina says, noting that postdoctoral researchers benefit from presenting their results to industry partners. ‘It’s good for them to learn what is relevant for industry, how the sector operates.’

Michael appreciates how the consortium helps build connections that shape future scientists: ’The connections and networks that master’s students, PhD students, and postdocs build during their time in ARC CBBC, along with the questions and inspiration they receive from different research groups and industrial partners, will shape their worldview, their approach to projects in industry, or the way they put together their own research groups if they remain in academia.’

Looking forward

As they prepare to launch the project, both researchers express enthusiasm about the learning opportunities it offers. For Ina, coatings represent a new research domain, and she looks forward to broadening her expertise. ‘I think we can learn a great deal from each other. It is also extremely valuable for postdoctoral researchers to be able to work in two very different laboratories and to learn from researchers with distinct yet complementary expertise.’

Postdoc Phoebe Lowy is keen to contribute her expertise to this multidisciplinary project. ‘I am particularly excited to work with industry leaders on the development of novel coatings,’ she says. ‘Having gained insight into sustainability challenges within the coatings industry, I am highly motivated to contribute to this collaborative application-driven research.’

While the researchers are realistic about the challenges ahead, they remain optimistic about achieving meaningful results. ‘We may not produce the ideal new coating, but I am confident that we will develop something innovative and gain valuable insights along the way,’ Ina says.

For Michael, the collaboration represents a valuable opportunity to apply his expertise to a practical challenge with significant environmental relevance. ‘We are very grateful for the opportunity provided by ARC CBBC, including the chance to work alongside Ina and explore new directions together.’

Broader significance

The work carried out by Ina and Michael demonstrates the value of partnerships that span academic disciplines and bridge the gap between university research and industrial application. For industry partners, such collaborative projects provide access to fundamental scientific insights that can fuel innovation. For academic researchers, they offer opportunities to ensure that their work addresses real-world needs and constraints. An equally important benefit is that these exchanges foster mutual inspiration: industrial challenges can prompt new academic research questions, while scientific breakthroughs can open unexpected avenues for industry.

As sustainability challenges grow more urgent, collaborative approaches of this kind – where diverse expertise with a shared focus on practical solutions are brought together – will be increasingly essential for developing the technologies required to support a more circular and sustainable future.